Vandermonde's identity

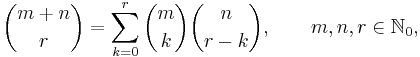

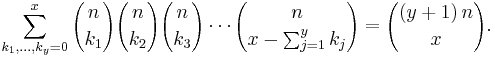

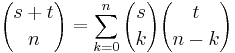

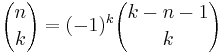

In combinatorics, Vandermonde's identity, or Vandermonde's convolution, named after Alexandre-Théophile Vandermonde (1772), states that

for binomial coefficients. This identity was given already in 1303 by the Chinese mathematician Zhu Shijie (Chu Shi-Chieh). See Askey 1975, pp. 59–60 for the history.

There is a q-analog to this theorem called the q-Vandermonde identity.

Contents |

Algebraic proof

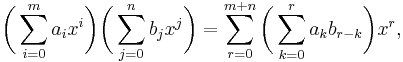

In general, the product of two polynomials with degrees m and n, respectively, is given by

where we use the convention that ai = 0 for all integers i > m and bj = 0 for all integers j > n. By the binomial theorem,

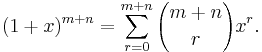

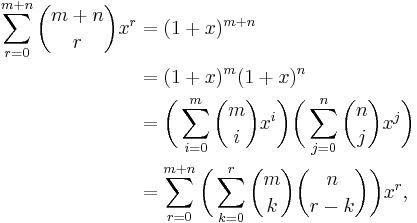

Using the binomial theorem also for the exponents m and n, and then the above formula for the product of polynomials, we obtain

where the above convention for the coefficients of the polynomials agrees with the definition of the binomial coefficients, because both give zero for all i > m and j > n, respectively.

By comparing coefficients of xr, Vandermonde's identity follows for all integers r with 0 ≤ r ≤ m + n. For larger integers r, both sides of Vandermonde's identity are zero due to the definition of binomial coefficients.

Combinatorial proof

Vandermonde's identity also admits a more combinatorics-flavored double counting proof, as follows. Suppose a committee in the US Senate consists of m Democrats and n Republicans. In how many ways can a subcommittee of r members be formed? The answer is of course

But on the other hand, the answer is the sum over all possible values of k, of the number of subcommittees consisting of k Democrats and r − k Republicans.

Generalized Vandermonde's identity

If in the algebraic derivation above more than two polynomials are used, it results in the generalized Vandermonde's identity. For y + 1 polynomials:

The hypergeometric probability distribution

When both sides have been divided by the expression on the left, so that the sum is 1, then the terms of the sum may be interpreted as probabilities. The resulting probability distribution is the hypergeometric distribution. That is the probability distribution of the number of red marbles in r draws without replacement from an urn containing n red and m blue marbles.

Chu–Vandermonde identity

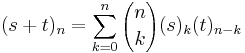

The identity generalizes to non-integer arguments. In this case, it is known as the Chu–Vandermonde identity (see Askey 1975, pp. 59–60) and takes the form

for general complex-valued s and t and any non-negative integer n. This identity may be re-written in terms of the falling Pochhammer symbols as

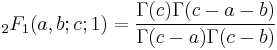

in which form it is clearly recognizable as an umbral variant of the binomial theorem. (For more on umbral variants of the binomial theorem, see binomial type) The Chu–Vandermonde identity can also be seen to be a special case of Gauss's hypergeometric theorem, which states that

where  is the hypergeometric function and

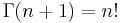

is the hypergeometric function and  is the gamma function. One regains the Chu–Vandermonde identity by taking a = −n and applying the identity

is the gamma function. One regains the Chu–Vandermonde identity by taking a = −n and applying the identity

liberally.

References

- Askey, Richard (1975), Orthogonal polynomials and special functions, Regional Conference Series in Applied Mathematics, 21, Philadelphia, PA: SIAM, pp. viii+110